The topic of welfare is a pressing concern in the field of poultry husbandry, influencing legislative and breeding systems globally. Welfare is a multifaceted concept that encompasses the physical and mental well-being of the animal, as well as the animal’s interaction with its environment (Martinez and von Nolting, 2023). In recent years, several welfare assessment protocols have been developed with the objective of evaluating the welfare level in a flock. To ensure the objectivity of these welfare assessment protocols, it is essential to define optimal criteria as well as optimal measures for these criteria. For example, Table 1 displays the principles, criteria, and measures of an exemplary welfare assessment protocol for poultry, as outlined by de Jong et al. (2016).

Table 1 The principles of welfare and the methods of their evaluation (de Jong et al., 2016)

| Principle | Criterion | Measures |

| Good feeding | Absence of prolonged hunger | Emaciation |

| Absence of prolonged thirst | Drinker space | |

| Good housing | Comfort around resting | Plumage cleanliness, litter quality, dust sheet test |

| Thermal comfort | Panting, huddling | |

| Ease of movement | Stocking density | |

| Good health | Absence of injuries | Lameness, hock burn, foot pad dermatitis, breast blister |

| Absence of diseases | Mortality, culls on farm, rejections on slaughter | |

| Absence of pain due to management procedures | Measure not developed | |

| Appropriate behaviour | Expression of social behaviour | Measure not developed |

| Expression of other behaviours | Cover on the range, free range | |

| Good human-animal relationship | Avoidance distance test | |

| Positive emotional state | Qualitative behavioural assessment |

Table 1 illustrates the complexity of welfare evaluation. Optimal growth is indicated by breeder-provided growth curves, which demonstrate high-level welfare in a flock. However, growth is compromised in the event of discomfort (Yang et al., 2011; Goo et al., 2019). It is noteworthy that growth performance is not included in developed welfare assessment protocols such as Welfare Quality®, AssureWel, and LayWel (Mels et al., 2023). This is surprising, since body weight and flock uniformity data is regularly recorded on farms, so its inclusion in welfare assessment protocols is relatively straightforward. Another issue is the duration of assessment protocols. For instance, the Welfare Quality® protocol involves evaluating 100 birds from a flock in numerous ways and takes approximately six to seven hours (Butterworth et al., 2009). Time requirements can often impede the practical implementation of such welfare assessment protocols by farmers and veterinarians. Consequently, there is a need for easy-to-use welfare assessment protocols that include the evaluation of growth performance.

The incorporation of growth performance evaluation into welfare assessment protocols

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated novel approaches to investigating the level of welfare in a flock in a more straightforward and accessible manner, suitable for use by farmers and veterinarians. Of them, assessing growth performance has shown great potential. The use of a manual poultry scale represents the gold standard for the precise evaluation of growth, while the use of automatic poultry scales represents a faster method for measuring the growth of a flock. Furthermore, automatic poultry scales can be employed in welfare assessment protocols, as demonstrated in a recent field study conducted by Mels et al. (2023). In their comprehensive field study, data was collected on 100 rearing pullet flocks raised on 28 different farms (11 conventional and 17 organic) located in Austria. The number of birds in each flock ranged from 14,251 to 52,400 on conventional farms and from 4,659 to 10,783 on organic farms. The animal-based indicators utilised in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Collected animal-based welfare indicators on farms (Mels et al., 2023)

| Animal based indicators (unit/levels) | Sampling strategy |

| Body temperature (°C) | 20 birds |

| Feather score (3 levels) | 15 birds |

| Bloody lesions (yes/no) | 15 birds |

| Avoidance distance (m) | 6 sampling points/flock |

| Reactivity score (3 levels) | Flock |

| Down feather present (3 levels) | Floor area |

| Uniformity (%) | Number of birds (500-3000) |

| Weight (g) | Number of birds (500-3000) |

| Mortality (%) | Flock |

| Disease in the period (yes/no) | Flock |

In the study, body weight and body weight uniformity (expressed as a percentage) were recorded using one BAT2 automatic scale per barn. To ensure accurate body weight evaluation, the automatic scale recorded the weight on the weighing platform at regular intervals. The scale was programmed to allow for a uniformity range of ±10% and to calculate body weight uniformity (%). On the day of the visit, the welfare assessment protocol was applied, and body weight and uniformity data from the previous 24 hours (ranging from 500 to 3000 birds weighed) was reviewed. The data pertaining to growth performance was readily accessible from the scales. This straightforward protocol can be readily employed by veterinarians during their visits and by farmers for the purpose of identifying potential issues within a flock.

The significance of incorporating growth performance into welfare assessment protocols was demonstrated by Sibanda et al. (2020), as evidenced by the differing levels of welfare markers observed across weight subpopulations in the flock. In the study, 7,708 laying hens were housed in aviaries and weighed individually using BAT1 manual scales. Following the weighing process, the data was downloaded from the scales and the laying hens were divided into three subpopulations based on their weight: light, medium, and heavy. The mean body weights for these subpopulations were 1.65 kg, 1.85 kg, and 2.08 kg, respectively. In summary, 55.8% of heavy hens exhibited single or multiple keel bone damage, compared to 48.9% and 50.7% of medium and light hens, respectively. The feather cover score on the breast of light hens was significantly higher (3.02) than that of medium (2.96) and heavy hens (2.87). The prevalence of gastrointestinal helminth infection was found to be highest in light hens, in comparison to that observed in medium and heavy hens. The incidence of fatty liver syndrome was found to be highest in heavy hens, followed by medium and light hens. Heavy and medium hens exhibited significantly higher rates of full egg follicle production (95.3% and 94.8%, respectively) compared to lighter hens (90.0%). The results indicate that flocks of lighter birds are more prone to welfare issues compared to those of heavier hens. Taken together, heavier hens are healthier, meaning that precision weighing can reveal potential welfare issues within the flock. Given its fixed nature in the breeding process, bird weight data can serve as a first-level indicator of issues that farmers can then investigate by evaluating other welfare indicators.

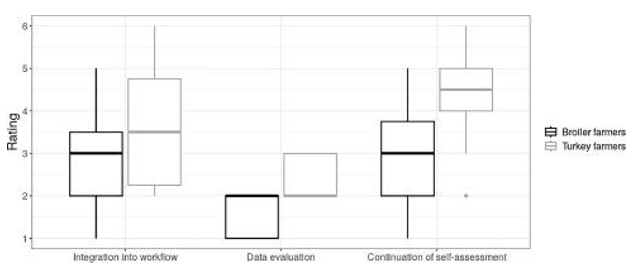

The application of weighing in welfare assessment protocols was also performed in broiler chickens and turkeys in a novel protocol, as reported by Michaelis et al. (2024). In their study, they developed a practical welfare assessment protocol that included an evaluation of growth performance. This protocol was tested directly on chicken and turkey farms. Subsequently, the participating farmers were trained and then the protocols, comprising 18 indicators for broilers and 20 indicators for turkeys, were tested on their farms for a period of one year. The weights of chickens and turkeys were evaluated using manual poultry scales with each sample containing 50 birds. During the weighing process, a 1–3-point scale was employed to assess additional welfare indicators and their respective levels. These observations were documented on paper. To establish a control measurement, the same parameters were simultaneously assessed by experienced scientists in conjunction with the farmers. The results demonstrated that all the farms exhibited various welfare issues. At the conclusion of the experimental period, the farmers were asked to assess the applicability of the welfare assessment protocol in their flock management (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The ease of integration of the welfare self-assessment into the farmers’ workflow was rated on a scale from 1 (very easy) to 6 (not at all easy). The evaluation of the self-assessment data was rated on a scale from 1 (very good) to 6 (very bad). Finally, the likelihood of continuing the self-assessment as recommended was rated on a scale from 1 (very likely) to 6 (unlikely) (Michaelis et al., 2024).

The figure demonstrates that the implementation of welfare assessment protocols into farm management is not yet widespread. The primary impediments were the time demands associated with the frequent scoring of birds, the comprehensive documentation of welfare data, and the subsequent processing and evaluation. The mean time required for the evaluation of individual animals in chickens was 51 minutes and 97 minutes for turkeys. The scoring of 18 and 20 parameters in chickens and turkeys, respectively, during weighing is a relatively time-consuming process. For time-related reasons, farmers can select individual indicators for the evaluation of specific problems within a flock. For example, in the case of cannibalism in laying hens or turkeys, the feather score can be evaluated. Similarly, in the case of litter quality, the food pad dermatitis score or hock burns can be evaluated.

The 5-point scale system incorporated in BAT1 poultry scales can be employed for the evaluation of individual parameters of welfare during weighing. Following the weighing process, the body weight, weight uniformity, and individual values (as indicated by the 5-point scale) for each bird can be readily downloaded from the scales, allowing for more efficient data evaluation. Consequently, the utilisation of a 5-point scale during the weighing process with BAT1 scales to assess welfare markers can enrich the evaluation of flock growth.

Welfare parameters evaluable during weighing

One advantage of manual weighing is that the person performing the weighing is in direct contact with the birds, which allows for the evaluation of additional characteristics that are clearly visible. As a result, the weighing process can be extended to evaluate welfare within a flock. It is recommended that a sample size of 100 birds from the flock be used for the evaluation of welfare parameters, with 10 birds from 10 different parts of the barn. Alternatively, evaluating these parameters during the weighing process would yield an even better overview of welfare, since samples used for weighing are typically larger than 100 birds and encompass 1–2% of a flock.

Walking ability

Walking issues can be attributed to a multitude of factors, including genetic predisposition, body weight, and management practices. It is widely acknowledged that the selective breeding of modern commercial broilers favours rapid growth and can therefore exacerbate these issues. The most prevalent musculoskeletal issues in broiler chickens are tibial dyschondroplasia, femoral head necrosis, and osteomyelitis. These conditions can result in suboptimal gait scores (Kwon et al., 2024).

The walking ability of chickens is scored using a gait scoring method. The most employed scoring system is a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating normal gait, agility, and the absence of gait problems. Conversely, chickens scoring 5 points are unable to walk. Chickens that receive a score of 5 points should be culled due to the unnecessary suffering that they experience (van der Sluis et al., 2021).

Gait scoring according to van der Sluis et al. (2021)

1 = Controlled, Stands straight on legs

2 = Walks well, Oriented

3 = More out of balance, can translocate well, but sits down quickly

4 = Walks with bent legs and waddles, walks with spread legs, legs outwards, wings often hang down

5 = Can only move by using wings

Feather coverage

In laying hens, feather score is typically used as an indicator of feather pecking, which can result in cannibalism. While scientists score birds on a 5-point scale, farmers find a simpler 3-point scale adequate for their needs. The evaluation may be conducted on various body parts. The scoring system employs a 1–5-point scale, with 1 representing birds that are almost featherless and 3- or 5-points representing birds with complete feather coverage. A downturn in feather coverage within a flock of laying hens is associated with an increased incidence of cannibalism (Labrash and Sheideler, 2005).

Feather coverage evaluation (Labrash and Sheideler, 2005).

1 = smooth and complete plumage

2 = ruffled, no naked spots

3 = naked spots up to 5 cm at the widest part

4 = naked spots greater than 5 cm wide

5 = naked spots with injury to skin.

Feather and body cleanliness

Body cleanliness is evaluated on a 3-point scale, with the ventral region of the body being the primary focus. The scoring system categorises chickens as either dirty or clean. The presence of faecal matter around the cloaca may indicate the presence of gastrointestinal disease, while a dirty breast area may indicate poor litter quality. The presence of dirt on chickens is indicative of suboptimal welfare (Saraiva et al., 2016).

Feather cleanliness scoring according to Saraiva et al. (2016)

1 = white feathers absent of dirt

2 = soiling feathers localised in the breast and abdominal areas without caked dirt

3 = generally dirty brown feathers sometimes with dirt adhered or caked to feathers

Hock burns

Hock burns are caused by an inflammatory dermatitis process that is visible on the hock joints in chickens. These are manifested by erythema of the joint, which is strongly correlated with a reduction in activity due to pain. An increased occurrence of hock burns is also indicative of suboptimal litter quality. The scale typically employed is a 5-point scale, with 1 representing a hock joint without any lesions and 5 representing a severe lesion evidenced by red hock joints (Arrazola and Torrey, 2021).

Hock burns scoring (Arrazola and Torrey, 2021)

1 = None visible

2 = One hock burn affected less than 0.25 cm2.

3 = Two or more hock burns, the largest less than 0.25 cm2.

4 = One hock burn equal to or larger than 0.25 cm2.

5 = Two or more hock burns equal to or larger than 0.25 cm2.

Food pad dermatitis

The assessment of food pad dermatitis is conducted visually and scored using a 5-point scale. A score of 1 represents a clean foot devoid of lesions and 5 signifies the presence of lesions on a significant portion of the foot and toes. The prevalence of these lesions was found to increase with poorer litter quality and the occurrence of pathogens, which ultimately resulted in a deterioration of the chickens‘ welfare (Arrazola and Torrey, 2021).

Food pad dermatitis evaluation (Arrazola and Torrey, 2021)

1 = None visible

2 = Lesion affected less than 25% of surface area without ulceration.

3 = Lesion affected 25% or more of surface area without ulceration.

4 = Lesion(s) affected less than 25% of surface area with ulceration, covered by crust/bumblefoot or swollen.

5 = Lesion(s) affected 25% or more of surface area with ulceration covered by crust/bumblefoot or swollen.

The scales can be arranged in accordance with the specific requirements of the farmers. The use of a 3-point scale is an acceptably straightforward approach for ascertaining the welfare of a flock. For more precise evaluation, the 5-point scale is recommended. However, it is important to note that observers must possess the requisite experience to accurately distinguish between the appropriate values.

Welfare evaluation is a complex process, with several new assessment protocols coming into practice over the last year. These protocols fall short of the ideal, however, given that they are time-consuming and omit growth as a useful indicator of flock comfort. The growth of a flock is a primary indicator of welfare, as only birds in optimal environments can flourish. Furthermore, specialised manual poultry scales like the BAT1 allow farmers to track other welfare indicators, such as fleshing score, during the weighing process, providing am even more enhanced insight into the wellbeing of their flocks.

Cited sources

Martinez, J., & von Nolting, C. (2023). Review: „Animal welfare“ – A European concept. Animal : an international journal of animal bioscience, 17 Suppl 4, 100839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2023.100839

de Jong, I. C., Hindle, V. A., Butterworth, A., Engel, B., Ferrari, P., Gunnink, H., Perez Moya, T., Tuyttens, F. A., & van Reenen, C. G. (2016). Simplifying the Welfare Quality® assessment protocol for broiler chicken welfare. Animal: an international journal of animal bioscience, 10(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731115001706

Mels, C., Niebuhr, K., Futschik, A., Rault, J. L., & Waiblinger, S. (2023). Development and evaluation of an animal health and welfare monitoring system for veterinary supervision of pullet farms. Preventive veterinary medicine, 217, 105929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2023.105929

Yang, X. J., Li, W. L., Feng, Y., & Yao, J. H. (2011). Effects of immune stress on growth performance, immunity, and cecal microflora in chickens. Poultry science, 90(12), 2740–2746. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2011-01591

Butterworth, A., Arnould, C., van Niekerk, T. (Eds.), 2009. Assessment protocol for poultry. Welfare Quality® Consortium, Lelystadt, Netherlands.

Sibanda, T. Z., Kolakshyapati, M., Walkden-Brown, S. W., de Souza Vilela, J., Courtice, J. M., & Ruhnke, I. (2020). Body weight subpopulations are associated with significantly different welfare, health and egg production status in Australian commercial free-range laying hens in an aviary system. European Poultry Science/Archiv für Geflügelkunde, 84(295).

Michaelis, S., Gieseke, D., & Knierim, U. (2024). Reliability, practicability and farmers’ acceptance of an animal welfare assessment protocol for broiler chickens and turkeys. Poultry Science, 103900.

van der Sluis, M., Ellen, E. D., de Klerk, B., Rodenburg, T. B., & de Haas, Y. (2021). The relationship between gait and automated recordings of individual broiler activity levels. Poultry science, 100(9), 101300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101300

LaBrash, L. F., & Scheideler, S. E. (2005). Farm feather condition score survey of commercial laying hens. Journal of applied poultry research, 14(4), 740-744.

Saraiva, S., Saraiva, C., & Stilwell, G. (2016). Feather conditions and clinical scores as indicators of broilers welfare at the slaughterhouse. Research in veterinary science, 107, 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2016.05.005

Arrazola, A., & Torrey, S. (2021). Welfare and performance of slower growing broiler breeders during rearing. Poultry science, 100(11), 101434.

Kwon, B. Y., Park, J., Kim, D. H., & Lee, K. W. (2024). Assessment of Welfare Problems in Broilers: Focus on Musculoskeletal Problems Associated with Their Rapid Growth. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 14(7), 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071116