Chicken meat is now one of the most affordable and widely available proteins in the world. This didn’t happen by accident—it’s the result of steady improvements in poultry breeding, health management, nutrition, and housing over many decades. By 2032, poultry meat is expected to make up 41% of all meat protein consumed globally, more than pork, beef, and lamb combined (OECD/FAO, 2023). Poultry farming also uses fewer resources than other types of meat production, making it a more environmentally sustainable choice.

Getting chicken from farm to table involves several connected steps, each one important for producing quality meat. The process starts with breeding programs that produce fertilized eggs from carefully selected parent birds. These eggs go to hatcheries where chicks are born. The young chickens are then moved to growing facilities where they’re raised until they reach the right weight for processing. Finally, they’re transported to processing plants where they’re prepared for sale. This whole process takes much longer than most people realize.

Breeding system

Modern poultry breeding is built on an important discovery made in the 1950s: chickens that are good at producing meat aren’t usually good at reproducing, and vice versa. This led breeders to develop separate male and female genetic lines that could be crossed to get the best of both traits.

Modern Breeding and Supply Chain

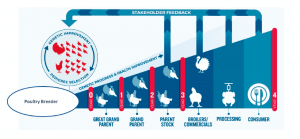

Today’s breeding programs work by selecting multiple genetic lines, each chosen for specific traits. From the initial selection to producing commercial chickens takes about four years. The system works like a pyramid (Figure 1), with the best breeding stock at the top. Genetic improvements made at the top level gradually spread down through several generations of birds.

Crossbreeding typically starts at the grandparent level, creating different types of chickens for different market needs. Breeders continuously gather feedback from farmers, processors, and consumers to adjust their breeding goals (Neeteson et al., 2023).

Figure 1: Structure of the breeding system (Neeteson et al., 2023)

Great grandparent stocks

At the top of the pyramid are the great grandparent chickens—the foundation of the entire breeding system. Broiler breeding mainly uses two breeds: Plymouth White chickens (maternal side) and Cornish White chickens (paternal side). Within these breeds, breeders maintain specialized lines of birds selected for valuable traits like high breast meat yield and efficient feed conversion.

The goals at this level include developing lines that excel at specific characteristics, figuring out which lines breed well together, expanding successful genetic lines, maintaining the quality of existing lines, and producing eggs for the next generation.

Grandparent stocks

This level involves breeding birds from the proven lines above. It’s the first crossbreeding step, combining genetics from great grandparent farms to create the foundation for parent stock.

Parent stock

Here, the second crossbreeding happens, creating the commercial hybrid chickens. These parent birds lay the eggs that will become the broiler chickens sold for meat.

Breeding goals

Modern breeding programs aim to improve multiple traits, not just growth speed. Each breeding program has specific goals based on what role that line will play in the final commercial bird.

Selection and Traits

For each trait breeders want to improve, they calculate an estimated breeding value for every bird being considered for breeding. This value combines the bird’s own performance with genetic information from its relatives and ancestors. How accurate these predictions are depends on how much information is available and how complex the trait is genetically.

Crossbreeding and Market Relevance

Commercial chicken breeds come from crossing three to four pure genetic lines. Each line is chosen for specific traits like growth rate, meat yield, or reproductive ability. The importance of different traits varies depending on what role each line plays in the final crossbreed.

For example, if a line is meant for slow-growing chickens, breeders won’t select it for fast growth. Modern breeding programs now consider animal health and welfare for all genetic lines, not just production traits. Setting these breeding goals requires thinking years ahead to make sure the breeds can adapt to changing market needs (Dawkins and Layton, 2012).

Hatcheries

Hatcheries turn fertilized eggs into day-old chicks for all levels of the breeding pyramid. The most important hatcheries are those that receive eggs from parent flocks and produce the final broiler chickens for meat production.

Two hybrid lines dominate worldwide: Ross 308 (developed by Aviagen) and Cobb 500 (created by Cobb Vantress). These are the most common broiler chickens used around the world (Giersberg et al., 2021).

Egg storage

When eggs arrive at the hatchery, they’re stored in large coolers kept at 10-15°C with controlled humidity. How long they’re stored depends on demand for chicks and how full the incubators are. Hatchery managers need to balance the number of eggs to keep incubators running efficiently while meeting delivery schedules (Giersberg et al., 2021).

Setting compartment

Incubation starts in the setting compartment, where conditions are precisely controlled. Eggs sit in trays with their blunt ends up and are rotated 90 degrees every hour. The temperature stays at 37.8°C with 55% humidity. Starting on day 10, controlled cooling begins. Three days before hatching, eggs are checked with bright lights (candling) and moved to hatching compartments.

Hatching compartment

The final stage happens in hatching compartments designed for when chicks emerge. Rotation stops three days before hatching (at 18 days for chickens). Eggs lie flat, and conditions shift to slightly cooler temperatures (36.6-37.0°C) with much higher humidity (65-90%).

Post hatch management

The time from the first chick hatching to the last—called the hatch window—should ideally be 24-36 hours. During this time, staff remove dried chicks, check their quality, sort them by sex if needed, and give them essential vaccinations.

Chick transport

Newly hatched chicks have a yolk sac in their abdomen that provides nutrients and water for up to 48 hours after hatching. If transport conditions are poor, chicks burn through this reserve faster, which can hurt their growth and productivity later. Reducing stress during transport improves chick welfare and growth potential (Yerpes et al., 2020).

Broiler farms

Modern broiler farms are where the final commercial chickens are raised to market weight. Today’s broiler houses (Figure 2) are designed for efficiency and animal welfare.

Figure 2: Example of modern broiler chicken house

Facility characteristics

Modern facilities are windowless buildings that hold 15,000 to 60,000 chickens each. They have advanced systems for controlling heating, ventilation, and air quality regardless of outside weather.

The buildings are used only for raising chickens and operate on continuous cycles. Each cycle includes a growing period of 32-38 days, followed by 7-14 days of cleaning and preparation. The „all-in-all-out“ system means all chickens leave at once, allowing for thorough cleaning between groups.

Stocking density and regulations

How many chickens can be housed together varies by country and local rules. According to Campbell et al. (2025), typical densities based on bird weight are:

– 17 kg/m² for birds under 2.0 kg

– 36.6 kg/m² for birds weighing 2.0-2.5 kg

– 41.5 kg/m² for birds weighing 2.51-3.4 kg

– 43.9 kg/m² for birds over 3.4 kg

Production cycles and nutrition

The timing allows for 6.5-7 complete growing cycles per year. During growth, chickens receive three or four different feed mixtures that change in texture and nutrient content to match their changing needs as they grow.

Chickens stay in these facilities until they reach about 2.5 kg, then they’re transported to processing plants.

Slaughterhouses and processing plants

Processing plants turn live birds into packaged meat through strictly regulated procedures that prioritize both animal welfare and food safety.

1. Bird Reception and Handling

When birds arrive, they’re kept in cool, protected areas where temperature and comfort are monitored. They’re unloaded in dimly lit rooms to reduce stress and kept close to the processing line. Industry standards require processing within two hours of arrival to maintain welfare and meat quality.

2. Stunning and Slaughter

Birds must be made unconscious before slaughter using approved methods like controlled atmosphere systems (CO2) or electrical waterbath stunning. After stunning, birds are killed through precise cuts to the jugular veins.

3. Processing

After bleeding, carcasses are dipped in hot water to loosen feathers, then mechanical pluckers remove all feathers. Internal organs are removed under sanitary conditions, and all carcasses are inspected for safety.

Rapid cooling follows to slow down bacteria growth. Finally, carcasses are cut into portions, inspected again, and packaged for sale (Dogan et al., 2022).

Meat quality

Chicken meat quality involves taste, texture, appearance, nutrition, hygiene, and processing properties. Factors affecting final meat quality can be traced back years before slaughter, showing how connected the whole production system is.

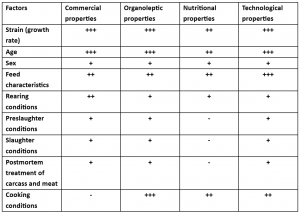

Breed and genetic lines are major factors affecting both growth and meat quality (Baéza et al., 2022). Table 1 shows how different factors impact meat quality.

Table 1. Impacts of various factors affecting the meat quality properties in broiler chickens (Baéza et al., 2022)

No effect (−), low effect (+), average effect (++), strong effect (+++)

Conclusion

Producing high-quality chicken meat takes about five years from breeding to finished product—much longer than most people think. Most of this time goes into careful genetic development and selection.

Every stage matters. The system works because each step builds on the ones before it, creating a chain where quality at every level contributes to the chicken meat that reaches stores and restaurants.

Delivering consistently high-quality chicken requires cooperation and precision at every stage. From geneticists working with breeding stock to processing plant workers ensuring food safety, everyone plays a part in a system that efficiently feeds billions of people while continuing to improve.

Cited sources

Baéza, E., Guillier, L., & Petracci, M. (2022). Production factors affecting poultry carcass and meat quality attributes. Animal, 16, 100331.

Campbell, Y. L., Walker, L. L., Bartz, B. M., Eckberg, J. O., & Pullin, A. N. (2025). Outdoor access versus conventional broiler chicken production: Updated review of animal welfare, food safety, and meat quality. Poultry Science, 104906.

Dawkins, M. S., & Layton, R. (2012). Breeding for better welfare: genetic goals for broiler chickens and their parents. Animal Welfare, 21(2), 147-155.

Dogan, O. B., Aditya, A., Ortuzar, J., Clarke, J., & Wang, B. (2022). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the efficacy of processing stages and interventions for controlling Campylobacter contamination during broiler chicken processing. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 21(1), 227-271.

Giersberg, M. F., Molenaar, R., de Jong, I. C., da Silva, C. S., van den Brand, H., Kemp, B., & Rodenburg, T. B. (2021). Effects of hatching system on the welfare of broiler chickens in early and later life. Poultry Science, 100(3), 100946.

Neeteson, A. M., Avendaño, S., Koerhuis, A., Duggan, B., Souza, E., Mason, J., … & Bailey, R. (2023). Evolutions in commercial meat poultry breeding. Animals, 13(19), 3150.

OECD/FAO (2023), OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023-2032, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/08801ab7-en.

Yerpes, M., Llonch, P., & Manteca, X. (2020). Effect of environmental conditions during transport on chick weight loss and mortality. Poultry science, 100(1), 129.